Bas-Reliefs: Betty Goodwin and Marie-Josée Chartier, the Improvised Narrative

Betty Goodwin (b.1923) is one of our most celebrated Canadian artists, with a career spanning over fifty years, and a compelling body of work that uses various media and techniques. Much has been written about Goodwin and her reoccurring themes of isolation, memory, pain and the human condition. In this essay I will reflect on how these themes are communicated, how Goodwin has created a narrative through her own creative oeuvre, and how the uses of improvisational narrative techniques relate not only to aspects of jazz, but to other communicative art forms such as dance.

Figures

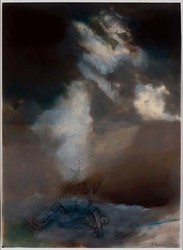

fig. 1

Betty Goodwin, Carbon, 1987, oil pastel, charcoal, pastel, wax, gouache on translucent mylar (geofilm), 301 x 215 cm irregular.

fig. 2

Betty Goodwin, Beyond Chaos No. 6, 1998, oil stick and charcoal on gelatin silver print on translucent mylar, 55.3 x 40.6 cm.

fig. 3

Betty Goodwin, Swimmers, c. 1980, drypoint in black and blue on laid paper, 32.5 x 35.8 cm.

fig. 4

fig. 5

Betty Goodwin, The Weight of Memory X, 1998, oil on stick on mylar, 21 x 24.7 x 10 cm. Collection of the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, Concordia University. Purchase - The Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Acquisition Endowment, 1998. Photography: Richard-Max Tremblay.

fig. 6

Bras de plomb. Paul-André Fortier. Costume and set by Betty Goodwin.

fig. 7

To see various photos of Marie-Josée Chartier please refer to:

fig. 8

Improvisation can be considered synonymous with jazz and musicians as they use improvisational techniques to relate and communicate with one another.1 I see the metaphor of jazz improvisation as a way of exploring how Goodwin’s images resonate and communicate with the viewer. As the viewer we are constantly constructing our own narratives in response to images. Improvisation is a medium through which we respond to the world. Our response to our everyday life is a form of narrative improvisation as we try to create meaning of our lives.

Goodwin’s figures have often been referred to as characters in a story. In his text Surely She’s Seen Me Looking at Them… Rober Racine poignantly demonstrates how the viewer’s response to Goodwin’s art work can be considered an improvisational response: (figs. 1 and 2)

“There is a solidarity, a complicity between the spectator and the work […] They are communicating; there is an interchange between them. Is this communication masculine or feminine? Is it human or animal? Is it in colour or in black and white? Sonorous or musical? Are [Goodwin’s characters] crying or howling? Are they joining or copulating? Do they have families? Will they drown? Can they support each other? Do they want to devour each other or kiss?”2

Goodwin herself has remarked that the works do relate to each other, that the pieces are woven together from many experiences.3 If we consider Goodwin’s series, the Swimmers (fig.3), Nerves (fig.4), and The Weight of Memory X, (fig.5) as agents of a narrative, we might also consider the transformative nature of the narratives in her work from one series to another. Goodwin’s visceral world is often characterized by the strength and fragility of her drawn figures. Invariably, her work has also made reference to the body whether she was working the canvas surface of her tarpaulins or drawing on paper like a skin.4

If we think of improvisation as a mediator of collective and individual memories, we can see how Goodwin’s her work is shaped by her reaction to the world and how her art is a way of responding to what she witnesses.5 In a broad sense, Goodwin’s response to the world is improvisational. Her reaction is then transformed into a creative process, which in turn highlights the concept of transformation as one of the defining qualities of improvisation. Goodwin is known for gathering diverse materials that she eventually uses to begin a project. In a sense, the process by which Goodwin collects artifacts for her art work, and how she improvises with different mediums, can be considered an improvisational technique in the same way a jazz musician will improvise with cues from his or her environment. Like the improvisational nature of jazz music, by acquiring the technique of improvisation, Goodwin is in fact creating through the techniques, and in the process of discovering what she is creating. “Technique” as it pertains to improvisation, must not only be considered merely a skill for developing new forms. In art forms such as theatre and dance, improvisation is also a means by which artists can express and present material to an audience in a totally spontaneous way.6

In response to Goodwin’s work, artists from other disciplines have improvised with her visual narratives. The result is the invention of a new improvised practice and the creation of new narratives. Communication and expression are rooted in the temporal nature of improvisation. Paradoxically, through improvisation, compositions are created. Canadian dancers and choreographers have encountered Goodwin’s world, inspired to retrieve narratives from the configuration of images in her work.

Montréal dancer-choreographer Paul-André Fortier observed Goodwin’s particular depiction of the human body:

“the wounded and broken bodies floating on immense, translucid backdrops of washed colours, the worn mutilated bodies sketched out, erased and redrawn, always in a state of tension; bodies cloven together or painfully alone; bodies in a state of movement, the movement of life.”7

In 1991 Fortier created La Tentation de la Transparence inspired by Goodwin’s work, and in 1993 Goodwin and Fortier collaborated on the creation of Bras de Plomb (Arms of Lead) (fig.6), for which Goodwin created the set design. As one might expect from the title, this was a dance about arms. In the design for the space Goodwin conceived a spare environment of metal geometric shapes in which to encase Fortier.8 Here, the process of collaboration can also be considered an improvisational technique where the two artists share a dialogue about the work they are creating. Each artist responds and improvises with the material offered to one another throughout the creative process.

Toronto-based French Canadian dancer-choreographer (fig.7), Marie-Josée Chartier’s improvisational encounter with Goodwin came from different kinds of settings. In 1998 Chartier attended the opening of the exhibition The Art of Betty Goodwin, at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. While performing in Regina, Chartier once again interacted with Goodwin’s work while visiting the MacKenzie Gallery, and she purchased the exhibition catalogue. Upon returning home, Chartier began to improvise with Goodwin’s images. Chartier focused on Goodwin’s Swimmer series. She reflected on how the figures appeared to be in an isolated space, how the periphery is never delineated, on the sense of gravity evoked by the figures, and on how the use of colour and texture accentuated the movement of the forms.

Although Chartier has collaborated with artists from disciplines in theatre and opera, Chartier did not wish to collaborate with Goodwin. Alternatively, Goodwin’s art was the point of contact and connection for Chartier to begin to develop her own images for a choreographic work. She improvised on the narrative of Goodwin’s work focusing especially on how the fluidity and weight of water in the Swimmer series. She created a vocabulary of dancing bodies with an emphasis on the movement of diagonal arms, the weight of one body leaning on another, and the idea of the body as a broken and heavy form.9 In 2003, Chartier created her own company, Chartier Danse, to support her artistic vision and creative endeavours. Still compelled by Goodwin’s work, Chartier immersed herself in transforming her images into dance. Using Elle a perdu son equilibre as a starting point, Chartier choreographed the duet La Lourdeur des Cendres (The Weight of Ashes). By improvising with Goodwin’s forms and the themes of memory, pain, and solitude, suggested by the movement of these forms, Chartier was able to uncover a new narrative. Chartier worked from the visual first, and from there proceeded to develop the movement. Thus, the physical vocabulary became an improvisation of the visual. La Lourdeur des Cendres was commissioned in 2003 by Four Chambers Dance Projects and premiered at Buddies In Bad Times Theatre in Toronto.

In 2006, Chartier was invited by Montréal’s Danse Cité to develop and premiere a new creation, Bas-Reliefs. Under the artistic direction of Chartier Danse, this project brought together eleven artists from Toronto and Montreal to collaborate on a multi-disciplinary project once again inspired by the work of Betty Goodwin. The artists, (two choreographers, two dancers, two composers, a videographer, and a scenographer,) worked together improvisationally, with one another and Goodwin’s work, to develop their own interpretation of Goodwin’s figures, and the formal elements of her compositions, such as colour, texture, line and space. Choreographers Ginette Laurin and Guillaume Bernardi each choreographed their own piece which was then performed in duet by Chartier and Dan Wild. Chartier envisioned Bas-Reliefs as two distinctive narratives that would relate to one another as two episodes of a narrative. Laurin’s piece is characterized by exhausting and repetitive physical passages of the body falling and drowning. Bernardi’s piece working in counter-point is more mythological and theatrical in nature. For example, the characters’ movements in the space appear directionless; their gestures are more pedestrian, as if the figures were replying to each other.

Referencing the visual basis of the dance, Chartier called Bas-Reliefs a diptych. Like a pair of thematically linked paintings, Chartier wanted to frame and define the two dance narratives as a diptych. In doing so, Chartier could link the narratives thematically, and use the visual art reference to acknowledge the inspiration drawn from Goodwin. With Bas-Reliefs, Chartier was interested in the idea of memory. She saw in Goodwin’s work how memory appeared like a mould, and how this mould could either be an empty space, or a space filled with the residue and traces of life. This in fact is the main reason the piece was named Bas-Reliefs.10 Bas-Relief, an architectural expression derived from the French, refers to a sculpting method which carves or etches away the surface resulting in a low relief. Chartier wanted the name to symbolize the image of something that is not unlike a fossil, to act as a metaphor for memory, to symbolize a space where something was once imbedded.

Chartier insists Bas-Reliefs was not a direct interpretation of Goodwin’s work. The artists of Bas-Reliefs, in response to Goodwin’s narratives, were able to explore, discover, and improvise in their own medium, which resulted in an improvisation with many of the elements in Goodwin’s work. This is reflected in the design and composition of Bas-Reliefs. We can trace the influences of Goodwin’s Vest and Nerve series in the costumes, and the Tarpaulin and Swimmer series in the geography of the set. The lighting and the videography is reminiscent of the dark figures in Goodwin’s charcoal sketches. (fig.8).

Further, the dancers in Bas-Reliefs, not unlike the characters seen in Goodwin’s work, are a male and female figure. The male figure is a character who exists in a mythological world; a non-descript landscape. His purpose is to receive the female figure – a victim – and to help her through a transition from one world to another. This narrative is strikingly portrayed in the physicality of the choreography and the gestural vocabulary between the figures. The audience cannot determine if the figures are pushing each other away, or pulling closer together, whether she is floating or drowning, whether he is a tender creature, or predator. As a narrative, Bas-Reliefs allows us, the audience, to not only personalize our experience, but to also improvise our own understanding of the experience. The improvisational concept of communication through art, whether it is dance, music or the visual arts, is in essence about looking beyond one’s own perspective to see, understand, and respond to the perspective of others.11

Like the characteristics of the improvisational narrative, “Goodwin’s art reminds us that art, however it is expressed, is rooted in connectedness to others. Its creation and our response, unites us in reflections on our experiences.”12 Goodwin’s art works, were a source of artifacts from which Chartier could begin to create her own narratives. Furthermore, if a narrative’s purpose is to preserve memory, bring mortality to our lived experiences, and communicate, then Chartier’s Bas-Reliefs contributes to the narrative by improvising with Goodwin’s work.

Endnotes

1 In his article “Jazz and the ‘Art’ of Medicine: Improvisation in the Medical Encounter,” Paul Haidet, MD, MPH, refers to G. Ward and K. Burns’, Jazz: A History of America’s Music. New York: Knopf/Random House, 2000 <http://annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/5/2/164>

2 Rober Racine, “Surely She’s Seen Me Looking at Them” in The Art of Betty Goodwin, eds. Jessica Bradley and Matthew Teitlebaum, 76-77 (Toronto: Art Gallery Of Ontario, 1998).

3 Sharon Doyle Driedger, “Bodies and Blood,” Maclean’s, 4 Dec 1995, 74.

4 Robert Enright, “A Bloodstream of Images,” Border Crossing, Fall 1995, 44.

5 Driedger, “Bodies and Blood,” 74.

6 Stephen Nachmanovitch, Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art. (New York, NY: Tarcher/Putnam, 1990) 9.

7 Aline Gelinas, “Bras de Plomb,” <http://www.fortier-danse.com/english.php>

8 Linda Howe-Beck, “Bras de Plomb: Dance Review,”

<<//findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1083/is_nl_v68/ai_14657100/print>>

9 Interview with Marie-Josee Chartier, October 29th 2007.

10 Ibid.

11 Lillian Eyre, “The Marriage of Music and Narrative: Explorations in Art, Therapy and Research.” <http://annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/5/2/164>

12 Matthew Teitlebaum, “The Mourner’s Cry”, in The Art of Betty Goodwin, eds. Jessica Bradley and Matthew Teitlebaum, (Toronto: Art Gallery Of Ontario, 1998) 35.

Bibliography

Bradley, Jessica and Matthew Teitlebaum, eds. The Art of Betty Goodwin. Toronto: Art Gallery Of Ontario, 1998.

Bradley, Jessica. Betty Goodwin: Signs of Life – Signes de vie. Windsor: Art Gallery of Windsor, 1995.

Chartier, Marie-Josée. Interviewed by Shauna Janssen, October 29th 2007.

Driedger, Sharon Doyle. “Bodies and Blood,” Maclean’s, 4 Dec 1995, 74.

Enright, Robert. “A Bloodstream of Images,” Border Crossing, Fall 1995, 42-53.

Eyre, Lillian. “The Marriage of Music and Narrative: Explorations in Art, Therapy and Research.” http://annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/5/2/164 (accessed November 2007)

Howe-Beck, Linda. “Bras de Plomb: Dance Review.” <<//findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1083/is_nl_v68/ai_14657100/print>>

Gelinas, Aline. “Bras de Plomb.” http://www.fortier-danse.com/english.php

Fortier, Paul-André. “Bras de Plomb.” http://www.fortier-danse.com/english.php (accessed November 2007)

Nachmanovitch, Stephen. Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art. New York, NY: Tarcher/Putnam, 1990.